【下記の日本語訳をご参照ください】

This article introduces the “Technology and Product in Context” course by Dr Betti Marenko held in the 2020/21 autumn term for GSEC, the Global Scientists and Engineers Course. The classes included a series of 6 lectures and a workshop with the students on the third week. Design theorist Dr Marenko is WRHI Specially Appointed Professor at Tokyo Tech and Reader in Design and Techno-Digital Futures at Central Saint Martins (CSM), University of the Arts London, UK.

What does it mean to be human in a world designed to be smart? How well can we get along with machines that are unpredictable and inscrutable? How do we think about ‘hybrid futures’? These were some of the questions raised in the Technology and Product in Context lecture series by design theorist, academic and educator Dr Betti Marenko. The course – ended in February 2021 – was attended by about 15 students from various branches of engineering, social and life sciences, who share an interest in the future of technology, philosophical issues around design and making, design theory and science communication. The sessions were conducted entirely in English and online, using Zoom, PowerPoint and Miro boards. This article follows the structure of the course and outlines some of the key topics, references and examples discussed each week.

Dr Marenko has written extensively about technological futures and the role of design in the Post-Anthropocene, a future geological era that does not presuppose the presence of humans on Earth. Her “tools for thinking in the Post-Anthropocene” lie at the intersection of design, philosophy and technology. In her view, the development of future technologies needs to engage with complexity, and design can benefit from a shift “from problem solving to problem finding”. The first lecture explored the question of hybrid futures from a historical perspective, tracing the origins of the human-machine encounter back to the automata that emerged in Europe in the Renaissance period.

Prompted by questions on their views on “technology” and “context” – two keywords in the course title – the students proposed ideas such as “the unknown”, “a more harmonious and convenient society”, abstract and changeable ideas of “hope”, “cooperation” and “unpredictability”. For Marenko, the context of design is not simply a background to a project, but “mutually constituted ecologies” of interactions that retain an ability to ask better questions. She highlights the undivided nature of theory and practice through the image of the Moebius strip, a continuous form that is both inside and outside. Similarly, the contrast between what is human and non-human, or post-human, is dissolved in philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s definition of the human as “the machine that produces the notion of the human”. For design theorists Colomina and Wigley, “being human means being able to design”, and design is about changing the world. For Marenko, the boundaries between human and non-human need constant reassessing, and technology is what we use to address this instability. The lecture included numerous examples of artworks and writings that illustrate or embody her philosophical narratives.

The course continued with an exploration of the concept of future through three keywords: expectation, imagination and anticipation. Anticipation is the capacity to imagine the non-existent future in the present, leading to the idea of ‘future proofing’. However, as Marenko puts it, “the conditions for change do change”. The simplistic assumption that future proofing is possible, let alone desirable, underpins some of the failed philosophies of modern design: planned obsolescence (the design of failure to stimulate future sales), solutionism (the idea that design is all about finding solutions to existing problems) and linear progress (the vision of a world constantly improving thanks to science and technology). Design brings better solutions, but better for whom? And, better for what? Dr Marenko proposes a view based on French philosopher Gilles Deleuze’s idea that building the future is not about predicting but “being attentive to the unknown knocking at the door”.

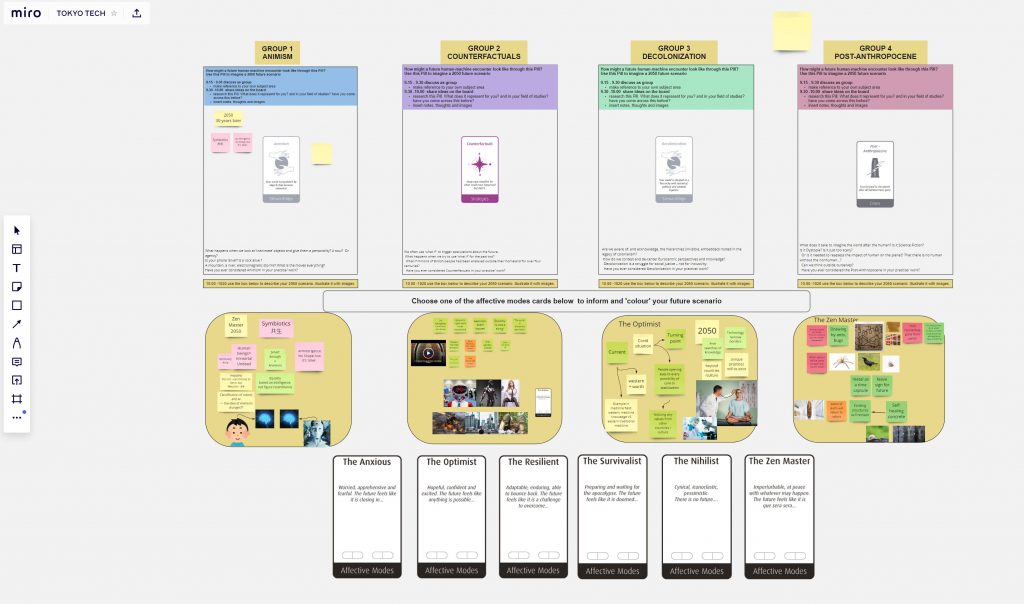

This set the basis for a workshop conducted on Week 3 using a Miro board and a set of cards developed by Dr Marenko and colleagues at CSM. Working in four small groups, the students were asked to propose a scenario for 2050 that addressed one of four ‘pills’ provided: animism, counterfactuals, decolonization and post-Anthropocene. These were read through selected ‘affective mode cards’, which summarised the attitude performed in the discussion, i.e. the anxious, the optimist, the resilient, the survivalist, the nihilist and the Zen master. Guided by this participatory strategy, the groups offered their visions of the future in short presentations, anticipating a few aspects that would be analysed in the subsequent weeks.

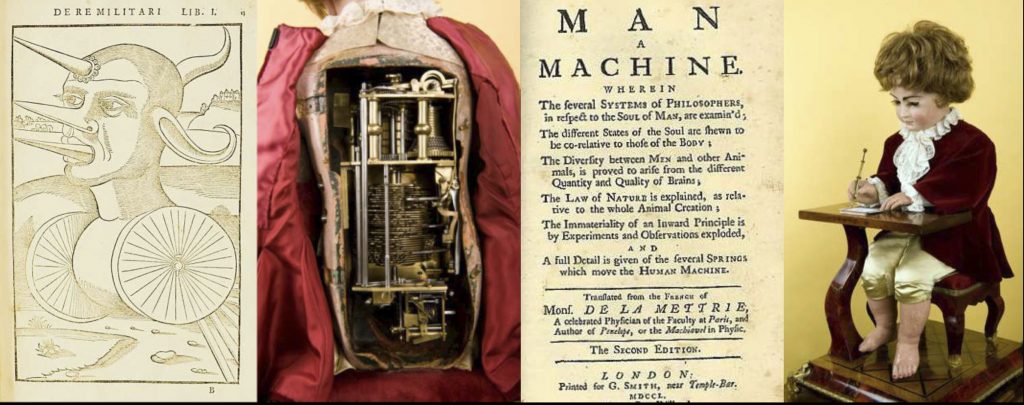

The course went on to question “received notions of technology” as having to do with the latest innovations, and stressed the continuity with historical developments. The term and notion of android, for instance, go back to Pierre Jaquet Droz’s writing automaton from the 1770s and its use of the power of technology to “enchant” its audience. Similarly, the term automaton today to some extent maintains the original meaning (from Diderot’s Encyclopaedia of 1751) of a machine that can move by itself, following a sequence of operations or responding to encoded instructions. The conversation continued on the topic of “digital enchantment” (based on texts by anthropologist Alfred Gell) and the relationship of technology with magic. The lecture material was grounded in historical and philosophical developments but made more accessible by recurrent references to well-known techno-gadgets, and visual and popular culture: from iPhones and Blade Runner, to Amazon and the latest Android firmware.

Following the steps of French philosopher F. Guattari, Dr Marenko discussed digital uncertainty in contemporary society, one that is seeing “a fundamental repositioning of human beings in relation to both their machinic and natural environments”. Information and computation are not simply mediating our lives, they constitute a large part of what we do every day. But the outcomes of these digital encounters are not fully predicted or programmed, hence the emergence of uncertainty. Examples include the algorithmic automation that drives financial services and much of our interaction online. These considerations are driving AI innovations and constitute a new “technological unconsciousness” that contrasts with 20th century views of technology. Marenko therefore asks, “Can AI get smarter by becoming more uncertain?”.

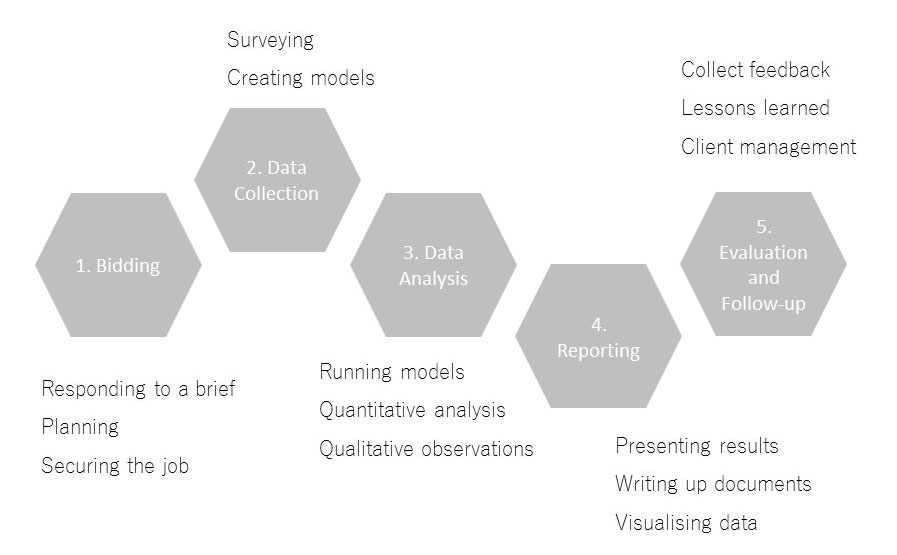

Through old and new theories of cybernetics, uncertainty was explored both as an accident and as a glitch. A fundamental concept is von Foerster’s “non-trivial machines”, deterministic systems producing unpredictable outcomes. Digital models, for example, can work by iterations and design strategies can operate by a fast succession of trial and error, as described by historian and critic Mario Carpo (2013). This poses interesting questions on what constitutes digital craft and how it relates to the idea of “risk”, an essential aspect of handmade production.

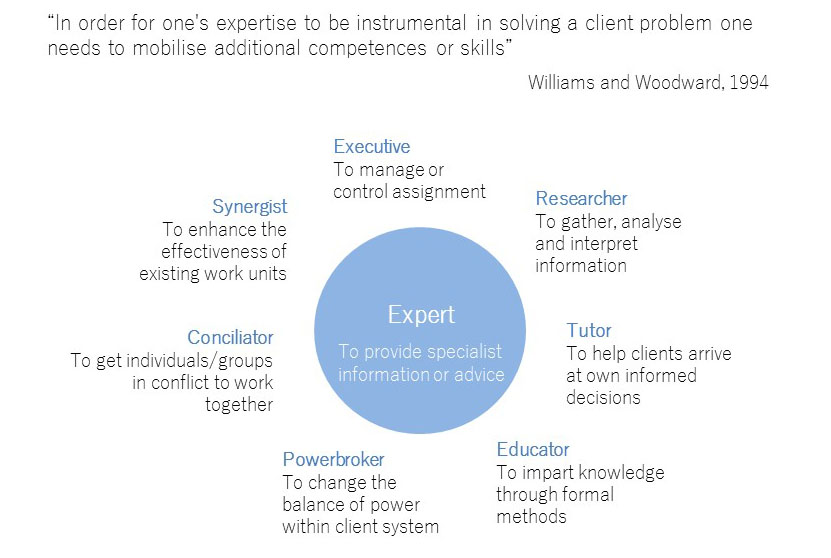

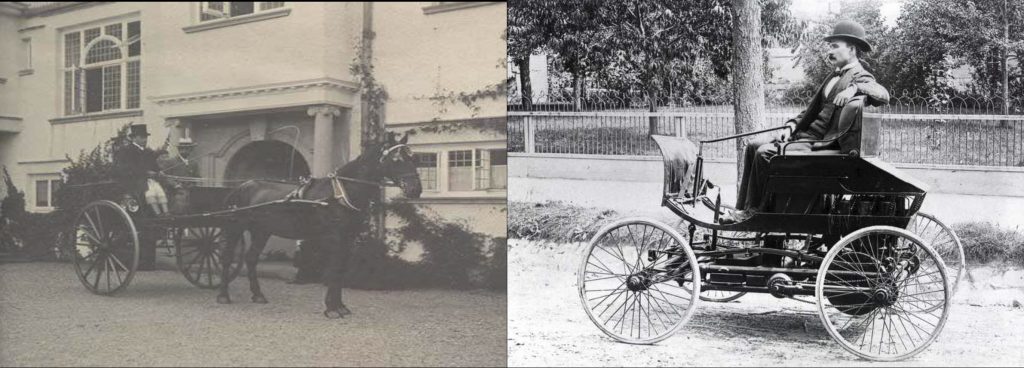

The next lecture started by pointing out the paradox of innovation: any new products must retain familiarity, so people can comprehend and recognise them. For example, the first car in the 1870s was named “the horseless carriage” and very much looked like one. Design theorists D. Norman and R. Verganti discussed this issue in their 2014 paper on “incremental and radical innovation”, a critique of the same human-centred design (UCD) that Normal had helped developing in the 1980s and 90s. For them, UCD can provide incremental innovation to “users” but only focuses on things people already know. For Marenko, instead, design can assume a more rhizomatic nature and embrace its role as interface between the making of objects and that of concepts. According to this view, the design process is simultaneously thing-making, concept-making and future-building.

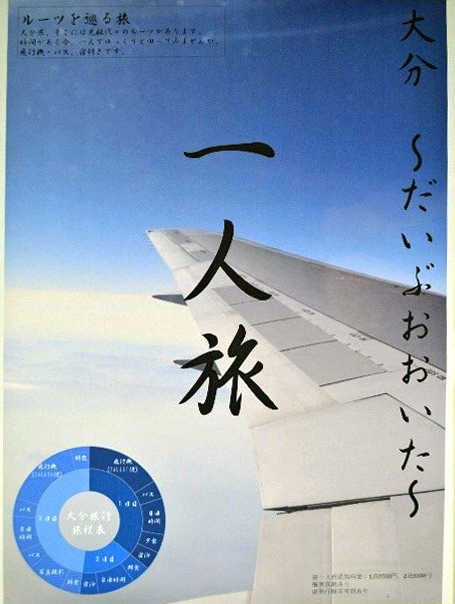

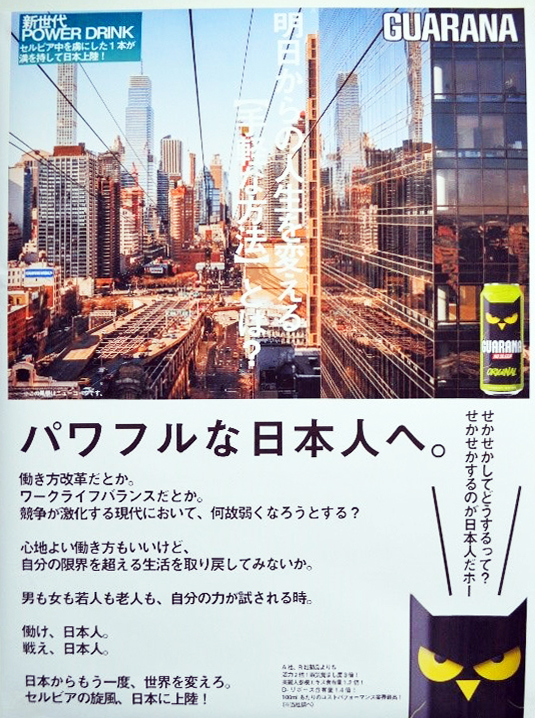

The discussion followed on the concept of future crafting and the role of fiction in producing reality. This was linked to other design strategies and methods of future crafting, such as cultural probes (embracing risk and uncertainty) and defamiliarization (embracing strangeness).

The series concluded with Dr Marenko’s original reflections on technology and animism. As surprising as it may sound, we already live in a world that has seen a shift from “talking about things to talking with things” (her italics). If from a technological perspective we are seeing the rise of the ‘internet of things’, theoretical developments also attempt to question outdated (Western) notions of animism for our new age. Following Bruno Latour’s thinking, the focus is not just on drawing parallels between consumerist and religious practices, but to rethink about the “agency” of objects as a relational property. Philosopher Jane Bennett has also discussed “thing-power”, the curious ability of inanimate things to produce effects. Referencing multiple recent studies on the subject, Dr Marenko discussed the role of animism in creativity and design. She provides a definition of “animistic design” as one that operates in a post-user (or post-UCD) scenario and maintains “mental elbowroom” to generate new, non-linear forms of knowledge. But why is uncertainty so important? Because it establishes perceptions, it shows what might happen and focuses on ranges of possibility, including those that were not thought of. It depends on elements that are not fully controllable, are random and not fully predicted. Uncertainty has to do with creativity.

Through her often surprising and always inspiring lectures, Dr Marenko opens new views on technology and its deployment in crafting humanity’s future. Her arguments on science and technology stand out as seamlessly built on a diverse range of references across disparate disciplines. The discussion was made more accurate and relevant by drawing from philosophy and design theory, but also science fiction, critical design, art practice, advertising and popular culture. The hope is that students’ accepted views of technology could be shaken by all this unorthodox transdisciplinarity, leading them to wider-open reflection, inspiration and future-shaping innovation.

Dr Betti Marenko’s forthcoming book, Designing Smart Objects in Everyday Life. Intelligences. Agencies. Ecologies (co-edited with Marco Rozendaal and Will Odom), is a collection of essays developing a new research framework for interaction design. For more information on this and other projects, visit bettimarenko.org

2021年1月7日から2月5日:ベティ・マレンコ博士による「物語のあるものつくり」

スマートになるように設計された世界で人間でいるとはどういう意味でしょうか?予測不可能で不可解なマシンとどれだけうまくやっていけるでしょうか?「ハイブリッド未来」についてどう思いますか?これらは、デザイン理論家、学者、教育者であるベティ・マレンコ博士(http://bettimarenko.org/)による「物語のあるものつくり」講義シリーズで提起された質問の一部でした。

コースは2020/21後期に開催されました。このコースは、Zoom、PowerPoint、Miroボードを使用して英語・オンラインで行われた6回の講義と3週目に行われる学生によるワークショップのシリーズでした。

一連の講義は、以下のトピックに基づいて展開されました。

- Post-Anthropoceneを推測するための理論的道具

- 将来の期待

- 「未来の哲学のピル」ワークショップ

- 人間と機械の出会い:アンドロイドからアルゴリズムへ

- 惑星計算におけるデジタルの不確実性

- スペキュレイティブ、フィクション、未来のクラフトをデザインする

- アニミズム2.0

マレンコ博士の驚きに溢れ、常に刺激的な講義を通じて、テクノロジーと人類の未来を創造する上でのテクノロジーの展開についての新しい見解が開かれます。学生が受け入れているテクノロジーに対する見方が、この非正統的な学際的研究によって揺さぶられ、より広い省察、インスピレーション、未来を形作るイノベーションにつながることを願っています。